Adults have long been squeamish over talking to children about sex. We have a history of complicated and conflicting attitudes: sex has been seen as simultaneously joyous and desirable (so long as it is between a young couple after marriage and in the interest of begetting babies), but also as dark and dirty, something from which children must be protected.

Religion and paternalism, rooted in a historic cult of virginity at marriage and the ownership of women, continue to influence the debate over sex and relationship education (SRE) around the globe. Even in countries such as the UK, many adults do not feel comfortable with the idea that children can have sexual feelings, particularly if they are LGBT feelings. The parents who object to the government plans for sex education in primary schools talk of the need to “protect childhood innocence”, as if sex is something corrupting or wrong.

And yet, SRE for children has the power to transform the world. For girls in particular, it is not just about identifying the functions of a penis and a vagina. It is about enabling her to become her own woman, giving her the confidence to speak as an equal: someone allowed to say no, who understands how to access and use contraception. That young woman is then primed to fight for a place in the world, with a job and the number of children she chooses, at the time that she prefers. No wonder male-dominated societies feel threatened.

But this genie won’t go back in the bottle. The catastrophic spread of Aids in Africa has led to widespread efforts to teach children about safe sex. Even in countries such as Uganda that refuse to countenance sex education in the classroom, it is happening via NGOs that have picked up the ball – literally – and are running with it. Here, football, traditionally for boys, has become a gender-leveller and an unlikely means to teach children about relationships and sexuality.

Most people accept that teaching children about sex does not mean they have sex earlier. In fact, it is quite the reverse – they learn how not to. And if grownups want to keep any control of the agenda, they need to act, because information about sex has never been more available. Television now does sex education in prime time, from MTV’s Shuga in Africa, a popular series exploring young people’s sexual issues and interactions, to Netflix’s hit drama Sex Education, about schoolkids’ first fumbling experiences.

And then there is the internet. No information-vacuum today goes unfilled. As Unesco said in updated guidance last year on comprehensive SRE: “Countries are increasingly acknowledging the importance of equipping young people with the knowledge and skills to make responsible choices in their lives, particularly in a context where they have greater exposure to sexually explicit material through the internet and other media.”

The progress on education about LGBT sexuality is slower. In many countries, gay sex can lead to prison, or even the death sentence. But in other societies, classroom discussions about boys who feel like girls and girls who want to be boys are increasingly taking place. Young people will demand no less. Last year, during the consultation over the UK government’s proposals, children told the International Planned Parenthood Federation (IPPF) that the sex education they received was too often based on scare stories. It was about managing a problem, rather than talking about a natural part of life. Nor did it address the identities and experiences of young LGBT people.

As the following stories from around the globe show, sex education is in everyone’s interest. It brings down birth rates and allows families to be smaller, with the means to educate their fewer children. It allows girls to become women before they start to have babies and it fosters good relationships between people of every and no sexual preference.

Sarah Boseley

Indonesia

Sex education is not mandatory in Indonesia. In addition, contraception for unmarried couples is difficult to get hold of and abortion is forbidden unless a woman’s life is at risk or, under certain circumstances, if she is raped. Because schools cannot be seen to encourage extramarital or LGBT sex, SRE is not taught, unless an NGO steps in. Rutgers, the Dutch NGO and specialist in sexual and reproductive health, runs sex education in 38 schools in seven areas in Indonesia. Its programme, which is for 12- to 14-year-olds, takes in sex, relationships, gender issues and emotions.

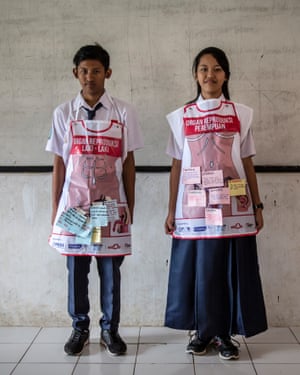

At SMPN 22, a school in Jakarta, children tell me the lessons provided by Rutgers are mostly made up of games. Muhammad, 13, says he enjoys them. “I learned about gender and myself,” he says. “I learned it’s OK to date, but you have to know your boundaries.” In one game, children pin body parts on to an apron worn by one of their classmates. Teachers make sure to include all body parts, because including only sexual organs could provoke complaints.

Fatma, 13, says she was initially nervous and couldn’t say the words “penis” or “vagina” aloud, but now she is comfortable talking about her body. Meilazzahara, 13, says she thought pictures of genitals were disgusting before taking part in the sessions. Her favourite game is “express yourself”, where the class pull different facial expressions to show their emotions. “My classmate’s faces were really funny,” she says.

Anita Rakhmi Shintasari, a teacher at SMPN 22, admits she was nervous before starting the sex education lessons. But, since they began, she has seen fewer children drop out because of child marriage or teenage pregnancy. Attendance is also better, because girls learn about menstrual hygiene. Narenda, 13, says she doesn’t skip classes any more, because she knows how often to change a sanitary towel. “I’m excited to go to school and want to go all the time,” she says.

In recent years, Rutgers has been forced by Indonesian conservatives to make several adaptations to the curriculum. It has had to take the word sex out of the title; scrap the brightly coloured cover of a textbook after it was criticised for being too like the LGBT rainbow flag; and redraw educational pictures of penises, after critics complained they were too big, too graphic and had too much pubic hair.

Discrimination against LGBT people is rising – the city of Pariaman on Sumatra island last year passed a sweeping regulation banning “acts that are considered LGBT”. To avoid a backlash, “we have to be very careful with the topics we discuss and the language we use”, says Nana Nur Jannah, a programme coordinator from Rutgers.

Despite the controversies, teachers, parents and pupils tell me they don’t want the lessons to stop. There is widespread violence against women in Indonesia, with 41% reporting that they have experienced physical, sexual, emotional or economic violence, and education is paramount in countering the attitudes that drive this.

Abby Young-Powell

Uganda

“I’m going to need a goalkeeper.” One hand shoots up and the rest of the players divide themselves into teams. On a pitch in Nsambya, Kampala, football is being used to teach children about sex. The international agency Soccer Without Borders has been working with child refugees in Uganda since 2008. It uses football as a vehicle for educational development all over the world, helping children of all ages to learn English and preparing them for school.

Once a week, Soccer Without Borders partners with the sexual health organisation Tackle Africa, which works across the continent to teach children about safe sex, reproductive health and consent. Younger groups are mixed gender, while older children are separated to help them feel at ease discussing tricky topics. These sessions offer young people space to ask questions that may be unwelcome elsewhere in the community.

Delphe Bahaya is leading a session on decision-making within relationships. The group of 10 girls, aged 14 to 16, have all fled conflict in the neighbouring Democratic Republic of the Congo. Most had never taken part in a team sport – and certainly never received any formal sex education. Uganda’s approach to the subject is to ignore it. In 2001, President Yoweri Museveni introduced a programme for sex education, the Presidential Initiative on AIDS Strategy for Communication to Youth (PIASCY), one of the central tenets of which was abstinence. In 2014, he signed an anti-homosexuality act, increasing the penalties for same-sex relationships, which have been criminalised since the colonial era, although the new law was later struck down by a constitutional court. Although HIV is the biggest killer of young people in Africa, discussing contraception is still considered taboo, in and out of education.

In Tackle Africa sessions, each football exercise is woven together with a lesson on sexual health. On the pitch, the girls start shooting with one defender, one attacker and one goalkeeper. Fifteen-year-old assistant coach Rita is in defence. She blocks the ball each time. They switch to two attackers, making things easier. “Come on girls, I want to see a goal,” she says. The girls get it past Rita, keep it under control, shoot and score.

Calling them in with the whistle, Bahaya links the exercise to sex ed. The choice to pass to your partner becomes the choice to use a condom. “The better you communicate, the safer your relationship will be,” he explains, after outlining the dangers of contracting HIV. “It’s up to both of you.” Scoring a goal shows they have reached their joint decision. As he is explaining, he uses the phrase “playing sex”. If you want to play sex, he says, you need to work together.

Tackle Africa’s drills normalise the language of sex, allowing the girls to ask questions without awkwardness. “Is it important to have sex?” one asks. “If you’re not ready, don’t,” Bahaya says. Another wonders: “If you’re married, do you still have to agree?” He nods. “You have to communicate and talk and agree.”

Soccer Without Borders and Tackle Africa have faced resistance from parents. It is often hard to get girls to play football, as they have family responsibilities that boys do not – cooking, cleaning, looking after younger siblings – and parents are often concerned about their bodies becoming too masculine. But, over time, myths about pregnancy, patriarchy and witchcraft have been countered with home visits and hard work. Now, some of the girls who have been through the programme are coaching the younger boys.

After the practice sessions, the students play a match. Programme manager Pius Kadapao tries to pinpoint why this model of learning works. “In school, sometimes the session becomes boring and you’re dozing.” He puts his hand out to stop a ball flying our way. “You can’t doze on a football pitch.”

Kate Wyver

Holland

“I am a big bear and I am in love,” says the teacher Betty van Zijtveld, drawing a bear on a large piece of paper. “I am not in love with another bear, but with a butterfly. But I’m too shy to say so. What can I do?”

Her four- and five-year-old pupils are thinking hard. “Wave at the butterfly?” one of them says. “Jump at it!” another suggests. “But that may scare the butterfly,” the teacher answers. “What can the bear do to express its feelings without chasing the butterfly away?” The children decide the bear should give flowers and enthusiastically start to draw them.

It’s Monday morning and in De Roos primary school in Amsterdam the “Spring Fever Week” has begun. This is a national initiative in which every Dutch primary school pupil receives daily lessons in relationships, sexuality and resilience. “We want to familiarise children with themes like feelings and sexuality at a very early age,” says Elsbeth Reitzema of Rutgers, which is funded by the Dutch government and initiated Spring Fever Week 14 years ago. “Research has shown that, when children learn about relationships and sexuality very young, they become sexually active at a later age and make well-informed choices,” she says. Open attitudes towards sex education in the Netherlands have led to the lowest number of teenage pregnancies in the EU: 3.2 in a thousand girls and falling. In the UK, the figure is 17.9, more than five times higher.

During Spring Fever Week, SRE is about more than simply explaining how reproduction works. The teachers discuss how to express feelings and set boundaries, but also sexual diversity, self-image and online perils. Each theme is taught in an age-appropriate way. The youngest pupils are told how babies are made, while older ones discuss problems such as sexual abuse.

When Marieke Hollander talks about sexual stereotyping with her class, who are between 10 and 12 years old, she reads a list of words and asks them which apply to boys and which to girls: “Sweet, sexy, caring, important, cool, self-assured.” “Important applies to girls,” one girl says. “Because women do everything: cooking, washing up, cleaning. All the important things.” A boy disagrees: “My mother is studying and my father does all the housework.”

Hollander goes on to show the children two adverts: one for women’s shampoo and one for men’s. The class agrees that the ad for women focuses primarily on beauty and that the male ad is all about being cool and self-assured. “Is there a difference between what you see in the ads and what you see at home?” Hollander asks. Most children think so. “With my parents it is the other way around,” answers a girl. “My mother isn’t very interested in looking beautiful, but my father has a good taste in clothes.”

“That’s true,” Hollander says. “It can be the other way round.”

In another classroom, Elly de Jong is discussing how to set boundaries with her pupils, who are eight years old. “You can like somebody, but still not want that person to come too close,” she says. One girl agrees immediately: “I hate it when my grandfather hugs me, because his beard stings.” Another girl says: “I have an aunt I hardly know and I don’t like it when she kisses me. It’s a strange feeling. And it’s sticky!” The whole class bursts out laughing.

“Your body is yours,” De Jong says. “And you decide what you want to do with it. So if you just want to shake hands with your aunt, that’s fine.”

Renate van der Zee

UK

“Wet dreams, erections and ejaculations – yes, it has been quite a full-on day so far.” Jess Hurst, a year five teacher at St Matthew’s primary school in Cambridge, is recapping the lesson on puberty she taught her nine- and 10-year-old students earlier that morning. “What else did we learn is going to happen?”

Hands confidently shoot up. “Hormones and emotional changes,” says one girl. “Discharge and periods,” says another. It is the fourth day of sex and relationships education week, which covers everything from the reproductive system to the need to challenge gender stereotypes.

St Matthew’s is a progressive urban state school, but all schools in the UK are set to follow its example from September 2020, when sex education will get its first update in nearly 20 years. Under new government guidelines, it will become compulsory for primary school pupils to be taught about healthy relationships, puberty and keeping safe online. Secondary school pupils will also be taught about grooming, sexual exploitation and domestic abuse, as well as STIs and the impact of viewing harmful content online. Female genital mutilation, eating disorders, drugs, alcohol, sharing private photos, sexuality and mental health problems are also among the topics that are deemed appropriate to discuss in lessons.

However, some parent groups have protested about the changes, with the lobby group Stop RSE calling for the government to “protect childhood innocence”. There have been other signs that sex education is still not controversy-free in the UK: one Birmingham primary school that taught pupils about LGBT rights as part of a programme to challenge homophobia was forced in March to suspend the lessons until a resolution can be reached with protesting parents.

Back in St Matthew’s, lessons on challenging gender stereotypes are taught by members of the Kite Trust, a local LGBT charity. Earlier this week, they spent an hour with pupils defining and then questioning how gender stereotypes have come about, whether they are true and how they make people feel. “Angry”, “devastated” and “uncomfortable” were some of the children’s conclusions.

Alongside this, they have learned about pubic hair, spots, toxic shock syndrome and which drawer of their teacher’s desk contains the free sanitary pads. Today, the class gather on the carpet as their teacher projects illustrations from Babette Cole’s picture book, Hair In Funny Places, and reads it aloud. “How do you think the character in the book feels when she discovers she is developing at a different pace to her friends?” asks Hurst. “Annoyed”, “worried”, “abnormal”, “confused” and “left out”, her pupils suggest.

“If you could talk to her, what would you say?” the teacher continues. “Everyone’s different. It doesn’t matter when you develop, it will still happen,” answers one child.

Afterwards, the class discuss the stages of puberty and sexual attraction detailed in the book. There are a few giggles, but in general there is a sense that talking openly about periods, breast development and erections with your teacher and members of the opposite sex is a perfectly easy, natural thing to do.

Donna Ferguson

India

“What would your parents think of you having sex?” A classroom of teenagers in Ghaziabad, a suburb of Delhi, ponder the question. Some giggle. Others go red. One girl finally raises her hand. “Sex can wait,” she says. “Career cannot.”

Sex education is rare in India. Until recently, most Bollywood films would cut to scenes of honeybees or butterflies communing when lovers retired to the bedroom. But such coyness does not translate to the wider culture – this is also the country where, in 2012, the gang-rape and murder of 23-year-old student Jyoti Singh shocked the world. Following that outrage, the number of reported rape cases jumped 26% in 2013. Meanwhile, convictions have remained stagnant. Illegal sex-selection abortions have led to a sex ratio imbalance of 112 boys born for every 100 girls (the norm is 105 boys to 100 girls). Such an imbalance is seen as a factor in crimes against women.

But inside this classroom, in a private school catering to wealthier families, students are given a rare opportunity to voice their hopes and fears about relationships, love and sex – guided by their lifeskills teacher, Renu Bhatia. Most say their parents do not characterise love and sex as immoral so much as impractical, getting in the way of preparing oneself for an extremely competitive job market. “Until you turn 18, you are completing your secondary education,” says Nishan, 17, relaying his parents’ views. “Then you move on to college, then you do another degree.”

Even when the time for romance arrives, it need not interrupt your studies, he says. “Your parents just click your photo and put it in the matrimonials in the newspaper,” he says. “Then, when you get married, they want you to have a kid. Season two begins.”

Each generation inherits a vastly different world from that of their parents, but in India the gap is especially large. Indians born since the late 1980s have grown up in a country flooded with western pop culture, the internet and promises their country will soon become a superpower. Old ideas about sex and relationships are under severe strain. But those ideas are newer than we think, says Rushi, 16. “Sex had been part of our culture,” she says. “We had the Kama Sutra, which is all about sex as a ritual.” Another student, Aahee, 17, blames the stuffy morals of the imperial power that ruled India until 1947. “We had the Britishers for many years and, in Christianity, sex is a sin,” she says. “Being oppressed by such a mindset, it will change you.”

Bhatia asks: “Who would be thrown out of their houses if their parents got to know they were in a relationship?” All hands rise. In this context, one of the biggest challenges the students say they face is getting reliable information about sex. Today’s generation has a decisive advantage over earlier ones. “Google is our biggest support,” says Aahee. “If we don’t have Google, we have nothing.” The other major source is India’s prolific film industry, which in the past decade has started exploring issues such as sex, women’s independence and LGBT Indians. “Bollywood is evolving,” Nishan says. “The audience is maturing.” Much of the sex education the students receive involves unravelling ideas of love and relationships gleaned from the big screen, Bhatia says.

The girls are warned against boys too eager to hold their hand or kiss them. “Be cautious, go away from this person,” Bhatia tells them. “Love can be at a distance. It doesn’t have to be a touchy kind of thing; don’t allow yourself to be taken for granted.” The boys are warned against giving into teenage obsessions, calling incessantly or “overloading a woman with gifts”.

So much is changing in India, “but the word sex still scares people off”, Rushi says. It is ironic, she adds, because lots of Indians must be having it. “We are the second most populated country in the world.”

Michael Safi

Nicaragua

To get a flavour of how sexual harassment might feel, a group of Nicaraguan boys are playing a game called “el puente”, meaning “the bridge”. The boys, aged between 14 and 18, stand in two lines, facing one another. One by one, each of them walks between the lines – crossing the bridge – while their classmates catcall, pester and stare at them. How do they feel when it’s their turn? Uncomfortable, they all say.

The workshops at the school in Managua, which focus on boys, are organised by the Samaritan Project, part of Redmas, a network of organisations in Nicaragua that work on the subject of masculinity, which is also part of MenEngage, a global alliance of NGOs and UN partners working to advance gender justice and human rights around the world. Today’s lessons for teenagers, at the Managua school, are made up of games, role play and exercises. The boys are taught about gender equality, toxic masculinity, sex and healthy relationships. They are also encouraged to respect LGBT people.

However, comprehensive sex and relationship education is not mandatory in Nicaragua and is often neglected, in schools and at home. This causes several problems, according to Hugo González, a regional representative from the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA). Nicaragua has a strong machismoculture, one of the highest rates of teenage pregnancy in Latin America, high rates of maternal mortality, and widespread sexual violence against girls, while abortion services are illegal. Boys often believe they should act in a stereotypically masculine way to impress each other, according to Ruben Reyes, who runs a programme for high schools. He says the aim of the workshops is to liberate boys from these macho beliefs, and to empower and make life easier for girls in the process.

Walter, 18, says he used to think girls had to “serve” men and do all household chores. Emmanuel, 18, says he believed boys had to be muscular and dominant. “If girls didn’t want to be more than friends, I would stop speaking to them,” he says. Boys also say they didn’t feel they needed to worry about contraception, as they couldn’t get pregnant.

A game that involves describing boys and girls to a pretend alien also helps challenge attitudes. “Typical responses are that girls do housework and boys go to work,” says Reyes, “so we address stereotypes.” Another game sees a “mailman” deliver letters to the pupils; the facilitator might say that all those who had sex the previous night have got mail. If they are brave enough, they stand up and take their post. The game is designed to get them talking openly.

The boys claim their behaviour has changed because of the lessons. Emmanuel says he now steps in when he sees girls being harassed and calls out friends who mistreat girlfriends. “I even encourage my female friends to play football to achieve their dreams,” he says.

Reyes explains many of the boys don’t like acting macho to begin with, but feel they have to in order to fit in. So, for many, the workshops come as a relief. The boys learn to empathise with girls, but they also shake off peer pressure to harass girls just to “prove” they are a man.

The boys’ relationships with each other have also improved: “I participate more with my friends,” says Einstein. “I’m more open with them, so they’re more open with me.”

[“source=theguardian”]

Techosta Where Tech Starts From

Techosta Where Tech Starts From